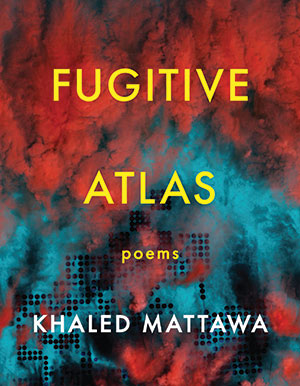

Fugitive Atlas by Khaled Mattawa

Minneapolis. Graywolf Press. 2020. 112 pages.

Minneapolis. Graywolf Press. 2020. 112 pages.

AN ATLAS IS A BOOK of maps and charts. But what would a “fugitive atlas” look like? In his fifth full-length collection of poems, MacArthur Award–winner Khaled Mattawa’s Fugitive Atlas draws a poetic weltbild, a world picture that makes room for the exiles, fugitives, migrants, and refugees who are often the victims of maps and the states that make them. Mattawa, who spent over thirty years in exile from his native Libya due to the toxic rule of its dictator, Muammar al-Qaddafi, has split a literary lifetime between writing his own poetry, lifting up Arab American writing, and translating the great contemporary Arab poets, many of whom who have also been exiles: Adonis, Fadhil al-Azzawi, Mahmoud Darwish, Saadi Youssef. In a way, Mattawa has been another kind of Atlas, the mythic one who bears the world on his shoulders.

After the publication of his award-winning Tocqueville in 2010, Fugitive Atlas maps the global dreams and madness of the last decade. Its structure is subtle and complex. Beginning and ending with sections that deal with the contemporary predicament of the Anthropocene and the ongoing trauma of terrorism, the book’s other sections include one that focuses on military and imperial occupation (from Palestine to Iraq to our own benighted city of Flint, a short drive from Mattawa’s Ann Arbor home); one section on Libya and its civil war; and a section on the predicament of migration across the Mediterranean. It’s a book that attempts to abide with so much heartbreak, the reader feels that the world has aged and gone gray by the time she finishes it. Such poems as “Anthropocene Hymns” feel like prophecy, and “Face”—about Iraq—feels like the embodied history we were never told.

Fugitive Atlas’s scope is global in theme and form; as an exile who has made his home in poetry, Mattawa stands at the nexus of American and Arab poetry, a cosmopolitan equally versed in the literature of West and East. One of the delights of the book is to feel Mattawa’s mastery in moving so gracefully in the poetic universe, yoking together Western and Eastern forms into new hybrids. His modified haibuns, a Japanese poetic form mastered by Basho, conclude with rengas (rather than haiku) that frequently collage a poet from the West and from the East. His adaptation of the ‘alam, a Bedouin oral form of poem, enables him to capture both a sense of exilic fragment and sanctuary space—depending on how one reads across or down the page.

The 2010s began with the short-term elixir of democratic hope expressed in the Arab Spring. Begun in Tunisia, it rapidly spread throughout the Arab world, toppling Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak and creating mass demonstrations elsewhere. Very quickly, hope turned into despair as dictatorial power cruelly reasserted itself. Instability and violence in Iraq and Afghanistan, civil war in Syria, and ongoing economic and political trouble on the African continent led to the largest number of refugees and migrants since the end of World War II. Today some eighty million people are refugees or internally displaced people—many of whom make a perilous journey from the Global South and East across the Mediterranean to Europe, which Mattawa gives witness to in his longest section of the book.

In Libya, the 2009 protests related to the Arab Spring turned into an active and violent rebellion by 2011 and the deposing of its dictator. At the very moment that millions were exiled, Mattawa was able to go home. What Mattawa finds in Libya, as the poems in the third section of Fugitive Atlas show, is that the exile’s homecoming is frequently bittersweet. In “After 42 Years,” his important occasional poem written in the days after the death of Qaddafi, Mattawa does not wax triumphant but reflects with an admixture of pain and remorse. The poem concludes:

Lord, how little our lives must be,

when so much can be buried lost,

dumped in a hole, forgotten dust!

What will

our aftermath

be then?

We wash our hands,

put on spotless clothes.

There is no “after” until we pray for

all the dead.

Mattawa registers the astonishment at how small Qaddafi became, hunted out of a water pipe and killed like a rat—but also, paradoxically, how small and lost his own people seemed. All those lives—all that history of loss—disappeared with the dictator’s death. Mattawa senses that, to make Libya whole again, to find an “after” and a “we,” huge wounds would have to be healed. I respect how this poem maintains its humanity in the face of revolutionary fervor and the natural desire for retribution. Mattawa shows us a harder path, the path of the exile who seeks return, not revenge.

Creating a vibrant society out of one so long sclerotic with fear and malaise would prove to be difficult. Mattawa’s own attempts at rebuilding the country through cultural interventions are stymied by fundamentalist bullies, whose threats cause his co-editor, Laila Maghrabi, to flee the country in exile because of their publication of a 2017 anthology of Libyan literature that included a sex scene. In the final section of the book, his “‘Alams for Sun on Shuttered Windows” laments the continuing burden of loving one’s troubled country: “history or future / a weight / you won’t shed” and “how you long to / live another / life in your life.”

Mattawa’s poetic vision of the world witnesses to cruelty and calls for kindness, notes the numbness and calls for beauty. One imagines that, were he never an exile, that he would write the purest love poems, the sweetest psalms. “Dear world,” he writes in “Psalm for the Volunteer,” “who am I to / condemn you?” In that poem, he ends: “Dear soul, / how am I / to repair you?”

What he has made with his fate, however, is what we need to hear—those of us still bubble-wrapped in privilege—that the cruelty of the world may take everything from you, but not your soul, not your love. In a book that begins with the burial of his mother, Fugitive Atlas ends with his daughter’s confident words:

“I’m teaching you how to entrust the world to me,” she says. “You don’t have to live forever to shield me from it.”

Editorial Note: Read Phillip’s essay on Northern Ireland from this issue.

Philip Metres has written numerous books, including Shrapnel Maps (2020). Awarded fellowships from the Guggenheim and Lannan Foundations, and three Arab American Book Awards, he is professor of English and director of the Peace, Justice, and Human Rights program at John Carroll University.