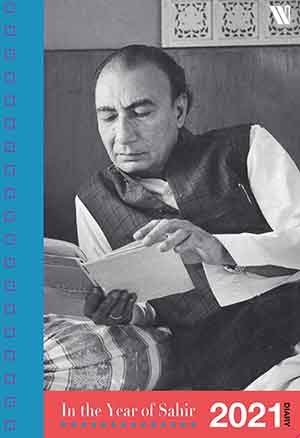

In the Year of Sahir: 2021 Diary by Nasreen Munni Kabir

Chennai, India. Westland. 2020. 144 pages.

Chennai, India. Westland. 2020. 144 pages.

MUCH OF INDIA’S LITERARY and cinematic worlds are geared up to celebrate with considerable enthusiasm the birth centenary of Sahir Ludhianvi (Abdul Hayee; 1921–1980), “a colossus among film lyricists,” considered by many as one of the foremost Urdu poets of the twentieth century. As her contribution to these festivities, Nasreen Munni Kabir, the eminent scholar of Indian film, has published this elegantly designed, spiral-bound, diary-like collection of reminiscences of Sahir’s many prominent friends and colleagues, numerous, never-before-published photographs, brief, incisive essays, remarks, and intriguing personal bits and pieces of sahiriana. For example, the back cover shows Sahir’s actual diary for August 23–26, 1978, along with his entry for the 24th: “Kaifi / Dinner – Faiz,” presumably a meeting with poet Kaifi Azmi (1919–2002) and dinner with poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911–1984).

Akshay Manwani, author of Sahir Ludhianvi: The People’s Poet (2013)—the best biography of the poet in English—introduces the volume with a concise essay that charts the trajectory of Sahir’s poetry from its beginnings to its etiolation in the 1970s. The diary concludes with Kabir’s incisive and contextualizing essay “The Story behind Parchhaiyan and Shadow Speaks,” which introduces a reprint of novelist/film director K. A. Abbas’s long-out-of-print English translation of one of Sahir’s most famous (and lengthiest) poems, the antiwar Parchhaiyan (Shadows; 1955), a harrowing account of what two young lovers experience during the terror of World War II. It appears side by side with the original text in Urdu script.

Sahir started writing poetry during his high school days and continued on into college, from which he was expelled for refusing to take his final exams as a political protest. He worked as a writer and subeditor of a number of major Urdu literary journals in Lahore, where he came in contact with young leftist-Marxist writers of the newly established, Soviet-inspired Progressive Movement. This group would dominate Urdu literature, as well as other major South Asian literatures, from the 1930s till the 1970s. On his first visit to Bombay in 1940, he came into contact with the Bombay film industry, many of whose most talented members were Progressives. There, his gifts as a writer of film lyrics (a number of which are essential for actors to lip-sync at intense or comic moments) were immediately recognized, and, over the next three decades, he became a major artistic icon in Indian cinema.

It was also at this time—the 1940s to the 1970s—that he wrote many of his most notable film lyrics, working closely with many of the Bombay film world’s major on-screen and behind-the-scene personalities. Some have commented about the poet especially for this publication. Remarks about Sahir made earlier by others, now deceased, are also included. Still others appear in many photographs. It’s a veritable who’s who of the Bombay film world: producer-director brothers B. R. and Yash Chopra; playback singers Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, and Sudha Malhotra; poet/lyricists Gulzar and Javed Akhtar; composers Zakir Hussain, Rajesh Roshan, and Shankar Mahadevan; actors Waheeda Rehman, Jaya Bachchan, and Naseeruddin Shah, to mention just a few.

Much of what others have said about Sahir in this diary suggests that he had a strong sense of self-worth. Though generous, he refused to be taken advantage of. He famously struck long-overdue blows for all underpaid, underappreciated artists when he demanded that producers pay him more for his songs and insisted that radio hosts announce the names of composers and lyricists of a song they were playing, not just the names of the singers. This acknowledgment was key in making the composers and lyricists of Indian film music famous across South Asia.

Carlo Coppola

University of California, Los Angeles