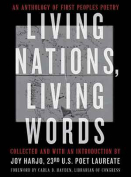

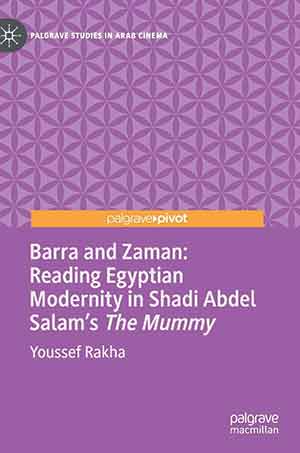

Barra and Zaman by Youssef Rakha

Cham, Switzerland. Palgrave Macmillan. 2020. 122 pages.

Cham, Switzerland. Palgrave Macmillan. 2020. 122 pages.

MORE THAN A book-length commentary on an Egyptian cinematic masterpiece, Barra and Zaman, part of the Palgrave Studies in Arab Cinema series, is a meditation on identity that wrestles with modernity, colonialism, and cultural ownership. The author takes the film, and himself, apart in two hundred short paragraphs.

Youssef Rakha, a well-known writer in both English and Arabic in his native Egypt, views Egyptian film director Shadi Abdel Salam’s classic The Mummy (also known as The Night of Counting the Years) through the twin lenses of the Arab Spring uprisings and Egypt’s modern history. His own personal struggles also flavor his viewing. The film is not a crowd-pleaser, but it was a darling of the film festival circuit when it was first released, and its cultural influence still looms large. It tells the true story of the discovery of a royal mummy cache in 1881 and the ensuing crisis for the protagonist, a member of the tomb-robbing clan who realizes that they are “trading in their own flesh.”

Some of those mummies were the very same ones that were paraded through the streets of Cairo this spring, before being welcomed into their new abode at the brand-new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. The director wanted to make films to eradicate what he saw as a “cultural and historical amnesia” in generations of Egyptians about their glorious ancient past. Of course, that will take a real investment in education, something neither the colonists nor their successors ever really bothered with.

Egyptology has long been the provenance of westerners, and its history is intertwined with colonialism. This is touched on in the film, but Rakha takes it much further, exposing all kinds of hidden stories. He then posits the provocative idea that Egyptians should accept colonialism as part of their national heritage, that nationalism couldn’t have existed without the very thing it set itself up against. We should not ignore being demeaned, he says, but we also shouldn’t make it our focus, that we are much more than that. Rakha suggests that identity is like mercury: try to grasp it and it will poison you.

Barra can be translated as “overseas,” “abroad,” “elsewhere.” Zaman means “in the past” or “long ago.” This is a reference to Egypt’s nostalgia for better times in the past, and things done better elsewhere, but it also lends a fantastical tinge to the title, as though it were the beginning of a fairy tale: “Long ago and far away . . . ,” as though the utopias glimpsed through space and time are unattainable for today’s modern Egyptians, and they shouldn’t even try. The film’s director was adamant that they were attainable, if only we could connect—the past with the present, the foreign with the local, the countryside with the city, the literate with the illiterate, the rich with the poor, the educated with the uneducated. Rakha does not necessarily agree, asserting that Abdel Salam indulged in wishful thinking. Some in 2011 believed in the fairy tale, imagining a better future and a better version of Egypt. The powers that be imposed a very different and painful reality.

Arthur Balfour once used Egyptology to justify British rule in Egypt by saying, “We know [the civilization of Egypt] more intimately [than the Egyptians themselves].” Egypt rightfully rejected that intimacy (well before the #MeToo era). Both Rakha and Abdel Salam seem to agree that Egypt has been “repeatedly reconstituted” like Osiris himself, and this constant theme of the revival of identity and of what it means to be “modern” is reason enough for optimism.

Jehanne Moharram

Norman, Oklahoma