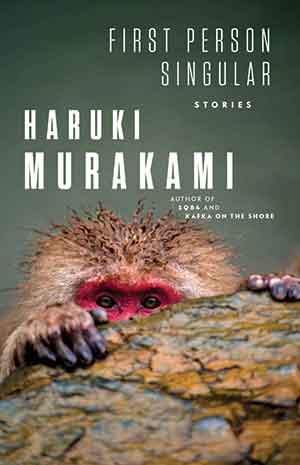

First Person Singular: Stories by Haruki Murakami

New York. Knopf. 2021. 256 pages.

New York. Knopf. 2021. 256 pages.

FIRST PERSON SINGULAR, a surprisingly poignant collection of eight short stories by Haruki Murakami (b. 1949), feels like an old book. It is not that the tales harken back to a bygone era, nor that five of the stories have appeared in other publications. Rather, the process of reading these vignettes brings to mind the fact that Murakami has been a published author for over four decades, and in their reading is a sense of reflection on a life lived and paths not taken. We get, therefore, a sense of the author’s age, his time in this world, and, perhaps, an intimation that his time, like everyone’s, is finite.

The presentation feels much as if Murakami were sitting with us, sharing recollections of moments in his past while we sip a cool beer. The tales spin out slowly, and the sense of distance gives them an ethereal quality that intensifies their subtle wistfulness. We see some of the magic realism here we have come to expect from this author, but by and large, they seem just this side of plausible, an oddly welcome change. They are soft around the edges, light and delicate without descending into vapidity, and ask us to think about the unimportant, random events in our own past that have, nonetheless, remained inexplicably with us. In creating this dynamic, Murakami is well served by his translator, Philip Gabriel, who has translated many of his works into English. He brings his usual deft touch to the renderings of these tales, all of which read easily, settling into the reader’s consciousness where their aftereffects linger pleasingly.

This is the first work to appear since 2017’s Men Without Women (see WLT, Nov. 2017), a collection I found wanting. The current work, by contrast, is gently satisfying. I was particularly taken by three. “With the Beatles” explores nostalgia, serendipity, and the complex interactions of unrequited desire with the inexorable progression of time. “Confessions of a Shinagawa Monkey” and the titular “First Person Singular” harken back to the Murakami we know. The former revels in its surrealistic exploration of the knowable and the self, while the latter throws the protagonist into a fantastic encounter of self-reflection that then aggressively withholds resolution.

In aggregate these stories offer up a fresh collection to remind us, once again, of Murakami’s singular appeal as the contemporary Japanese author best known internationally.

Erik R. Lofgren

Bucknell University