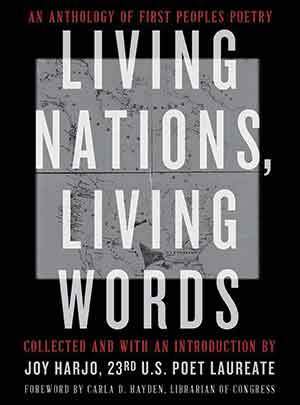

Living Nations, Living Words: An Anthology of First Peoples Poetry

New York. W. W. Norton. 2021. 240 pages.

New York. W. W. Norton. 2021. 240 pages.

LIVING NATIONS, LIVING WORDS is a project conceived of and curated by US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo and sponsored by the Library of Congress. In her introduction to the project, Harjo writes that Native Americans are “known from false images and narratives.” This project refutes and replaces colonialism’s narratives while, at the same time, it offers a selection of exceptional contemporary poetry.

Living Nations, Living Words consists of a print anthology and a beautifully designed multimedia website featuring an interactive map. Despite the use of a map, Harjo states that the project is “not organized around geography.” Instead, it’s oriented around a thick concept of place: places that are, at once, physical, cultural, temporal, and philosophical locations. Markers on the map indicate physical locations poets chose for themselves. Some chose traditional or relocation tribal homelands; some chose to place their marker where they live now, whether tribal homelands or not. The map, which does not include state boundaries, creates an intuitive spatial representation of Indian Country.

Visitors to the online project are guided to click map markers that reveal the selected poet’s bio and a link to audio files and PDFs of the poet reading and discussing their poem. The print anthology adds another layer to the map by placing poems in philosophical locations. For example, Deborah Miranda, an enrolled member of Monterey’s Costanoan Esselen Nation who lives in Virginia, maps herself to her tribal homeland on the West Coast, but, because her scathingly wry poem refers back to the beginnings of colonization, it is located in the “East / Beginnings” section of the anthology.

Jake Skeets and his poem “Daybreak” open the print anthology. The imagery in “Daybreak” springs from a palimpsestic perception of the interactions of place, self, and culture, “A basketball backboard crafted from sheet metal and piping // the ground crickets beneath moths telling a story as butterflies.” Heather Cahoon’s poem, “Baby Out of Cut-Open Woman,” begins with a traditional story of the being “whose actions brought an end to the last Ice Age.” After relating the story, Cahoon writes, “These are the stories that belong here / that pushed up through this soil unfurling” like “arrow-leaved balsamroot . . . and boulders found / in unusual / places.” Both Skeets’s layered poem and Cahoon’s poem, with its organic imagery and its boulder poems, enact the philosophy of the anthology as a whole.

Two poets, Craig Santos Perez and Lehua M. Taitano, are CHamoru of Guam, an island that, after the Spanish-American War, was transferred to the US navy by the Treaty of Paris (1898). In his narrative of displacement, Perez writes, “We attend American schools, eat American food, // . . . learn American history, . . . // . . . and die in American wars.” Taitano’s poem, propelled by the fact that “the conventional symbol for current is I,” explodes across eleven pages, words as signs scattered and mapped with the poem’s own coordinates. In both its style and its intellectual range, “Current, I” may remind readers of the “Thorow” section of Susan Howe’s Singularities, but Taitano’s poetics are not merely a version of others’—it is entirely her own.

Living Nations, Living Words includes several poems that reveal colonization’s infection of personal and family relationships. Tanaya Winder’s poem, “like any good indian woman” (first published in May 2017 in the “New Native Writing” issue of WLT), makes use of her experience in spoken-word. The running-breath line of the poem leaves a reader’s body exhausted like the bodies of the good Indian women she writes about, those who “burn like a phoenix” to pull their brothers away from bottles and car wrecks and suicides, away from word bullets and real bullets.

In Cathy Tagnak Rexford’s “Anchorage, 1989,” Brandy Nālani McDougall’s “This Island on Which I Love You,” and No’u Revilla’s “Shapeshifters,” the damage to relationships is laid bare and, sometimes, healed. Natalie Diaz’s “Postcolonial Love Poem” closes the “West / Departure” section and ends the book. Departure contains within it the idea of the future; “Postcolonial Love Poem” suggests that it is through conscious acts of love that the future becomes possible. Poetry and ritual, as Carrie Ayagaduk Ojanen reminds us, are practices that can decolonize relationships and heal what’s been broken.

. . . a small gathering of poets

each of us making, just so, our small figures

to be carried

what we are making cannot be undone

Living Nations, Living Words is an exceptional example of how digital humanities can engage with a broader audience than a book alone would reach. Readers will certainly wish to further explore each poet’s work and will be pleased to discover that all the poets have book publications except one, St. Croix Chippewa b. william bearhart. He passed away in 2020, during the production of the anthology. His poem, “Transplant: After Georgia O’Keeffe’s Pelvis IV, 1944,” is a stunning work; his death is a profound loss to poetry and to the Native writing community.

Harjo’s organizational principle, combined with her curatorial acumen, facilitates classroom use of Living Nations, Living Words. The project’s remapping of the United States recommends it for use in regional literature courses as well as cultural geography courses. As a textbook for Native literature courses, the project spotlights Native writing communities and a body of writing that has existed, in its modern form, since the mid-1700s. For cultural/religious courses and environmental literature courses, the project presents a complex, nuanced view of Native beliefs and practices, demonstrating that story serves to tie people to land, to culture, to philosophy, and to religion. Story situates us in our habitat as just one among millions of earth’s inhabitants.

The Living Nations, Living Words project reflects Joy Harjo’s commitment to poetry and to teaching. It extends her decades-long mentorship and support of Native people by refuting false narratives and by inscribing Native writers into the book of American poetry.

Jeanetta Calhoun Mish was the 2017–2020 Oklahoma State Poet Laureate, and in 2019 she was awarded a Poets Laureate Fellowship from the Academy of American Poets. Her recent books are a poetry collection, What I Learned at the War, and Oklahomeland: Essays. Dr. Mish is a faculty mentor for the Red Earth Creative Writing MFA at Oklahoma City University.

Jeanetta Calhoun Mish was the 2017–2020 Oklahoma State Poet Laureate, and in 2019 she was awarded a Poets Laureate Fellowship from the Academy of American Poets. Her recent books are a poetry collection, What I Learned at the War, and Oklahomeland: Essays. Dr. Mish is a faculty mentor for the Red Earth Creative Writing MFA at Oklahoma City University.