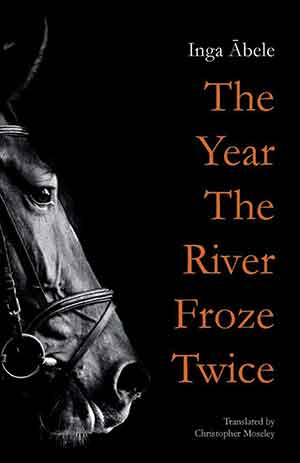

The Year the River Froze Twice by Inga Ābele

Norvik Press. 2020. 458 pages.

Norvik Press. 2020. 458 pages.

WORLD WAR II and its immediate ramifications are two of the most oft-treated subjects in anglophone popular fiction. It is still rare, however, to find an English-language novel that focuses on this period’s nuance and human cost for the countries subsumed by the Soviet Union. Translator Christopher Moseley embraces the uniqueness of Baltic languages in translating The Year the River Froze Twice from the Latvian, showing every fine facet of Inga Ābele’s storytelling. In its strength, this manifests as gorgeously illustrative language; in its shortcomings, this makes for a density of detail so concentrated it proves difficult for non-Latvian readers to parse.

In the opening, former jockey Andrievs Radvilis, having been sought out by a young female journalist, is persuaded by her to follow the stream of his memory. What flows out is an intricate portrayal of Radvilis’s life in Soviet-occupied Latvia, where he fiercely strives to maintain his independence of thought. Among the rarely discussed historical facets Ābele’s novel illuminates are the deportation of “undesirable” Latvians by secret KGB operations, the intricacies of social relationships for those outside the government under USSR rule, and the regional differences within Latvia and Latgale, both historically and today.

Where both Ābele’s writing and Moseley’s translation shine are in the seamless flow between plot and imagery. Sentences like “The girls’ faces become translucent, illuminated by the sap of life as if by oranges cast in bronze” are apt to catch readers by surprise amidst paragraphs of realistically rendered desolation. This is also where the novel reveals its necessity for some prerequisite understanding, however: images like this can be obtuse, and very little of the book’s length is given to scene-setting, so those unfamiliar with Latvian geography or language will likely get lost in the unusual turns of phrase and extensively researched details. It is also worth noting that neither Ābele nor Moseley flinches from using period-accurate language that not infrequently includes slurs and bigoted generalizations.

As the narrator, Andrievs, notes in a rare moment of interiority, “History is as secure a refuge as a hay-rack in a storm, and yet, it is a refuge.” The refuge of World War II–era history, so long confined to anglophone experiences, is being brought into the light by Ābele and Moseley in this volume, in all its grit and complexity.

Linda Stack-Nelson

Minneapolis