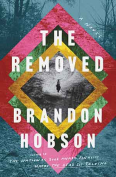

Poems of Hwang Yuwon, Ha Jaeyoun, and Seo Dae-Kyung

Sydney. Vagabond Press. 2020. 90 pages.

Sydney. Vagabond Press. 2020. 90 pages.

IN A POST-TEXTUAL, epidemic-prone milieu swarming with algorithm and AI, the imagistic texts from these three emerging, prizewinning young Korean poets catalyze the energetic (and perhaps equally enervating) kinetics of those new social modalities arising in Korea into the early twenty-first century. The responsiveness of Hwang Yuwon, Ha Jaeyoun, and Seo Dae-Kyung seems founded equally in anxiety and assurance for, as editor Jake Levine asserts, these poems parlay a “contradictory oscillation between personal hopelessness and collective hopefulness [which deploys] irony in order to survive precarious and meaningless employment, but still harbors the desire for both modernist political projects, large-scale social changes, and romantic and sincere feelings.”

Indeed, each of the three poets in this anthology materializes an interrogation of how to exist in an age of prevailing uncertainties. Hwang Yuwon’s so-called maximalist poems partly engage a sardonic vision of the sublime; drinking rice wine beside towering buildings, the poet notices how “the wind that blows / is more sea than sea / and more windy than the wind.” But beyond these Platonic preternaturalisms, Hwang scours experience for deeper meaning. In “Deep in the Heart of the Mountains,” he recalls how “I once came here with a different woman, / and yes, you once came here with a different man, but now, we can say we came here together too,” before arriving at a moment of penetrating stillness: “Don’t put so much value on it, on / me, the wind / just departed / after shaking / the tip of a branch / of that empty tree.” While some may read Hwang’s evanescence as nihilism, from another angle we might just as easily call the vision of impermanence a moment of transcending realization. In excessive, overburdened settings, intimacies are to be fleeting, and arbitrary.

Ha Jaeyoun’s stranger meditations endlessly defamiliarize the self as a socially regulated unit of subjective performance. And like Hwang, this poet’s materializations also lie somewhere between hyperrealism and the surreal, as if scouring the city’s environs for some kind of succor. In “A Dining Table for the Clouds,” Ha writes that the “thing I sometimes invite to eat at my table / Is a cloud,” and this is indicative of Ha’s delightful oddness, which remains sharply purposeful, the cloud a subsidiary to the tinned sardines in this poem’s center, a means by which to heighten the weirdness of a preserved can packed with “blue pickled death.” Ha’s text is quietly implicative, virtuosically so: surely it is as bizarre to eat from a tin of massed and purposefully “processed” beings as it is to do so in the presence of cloud-as-dining-companion.

Seo Dae-Kyung’s longer prose poems resemble works of microfiction, though thematically this poet labors similarly to both Hwang and Ha: for Seo, too, the self is a site ready for defamiliarization—“[o]ne fall night I puked up a monkey”—and he seems equally invested in critiquing identities displaced and subjugated by the rigors of turbo-capitalism: “We work as expected. It’s always the same. We work until a fucking portal opens.” Across these longer narratives, Seo understands that “I am dead. To speak accurately, I have travelled from many dreams into a single dream. I walk around the ceiling, the wind cack-cackling and the windows shake.” This captures an innately Korean tone, and Seo’s elaborations of a zombified state bespeak a living death taking place within what many young Koreans, fatefully and in resignation, call “hell Joseon.”

Most certainly, these are poets to watch, as is the Asia Pacific Poetry Series from Vagabond Press, which promises to continue bringing to our attention stridently new modes of poetic response. As Levine asserts: “What we are presented with in contemporary [Korean] poetry is absence and ambivalence, cultural appropriation, non-linear narrativity and genre-mixing.” The linguistic inventions from the Korean poets presented here are idiosyncratic interventions asserting an intersubjective humanity; in their own ways, each poet in this book speaks generatively toward the posthuman.

Dan Disney

Sogang University (Seoul)