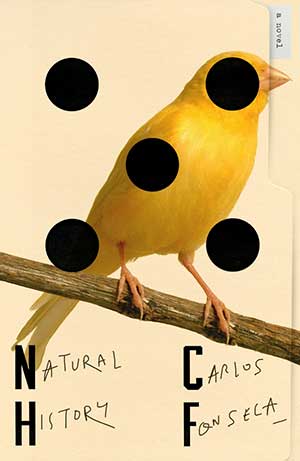

Natural History by Carlos Fonseca

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2020. 320 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2020. 320 pages.

MIDWAY THROUGH Carlos Fonseca’s new novel, an actress who has exchanged the limelight for a sprawling, subversive art project summarizes her views on innovation and mythmaking. “The only true artwork is disappearance itself,” the notorious Virginia McCallister writes in her journal—which can and will be used against her in a court of law.

Natural History toggles between a verdant Guatemalan jungle, a stagnant Pennsylvania mining town, a posh loft in New York City, and a neglected San Juan high-rise claimed by poor families. The action takes place in the 1950s, the ’70s, the ’90s, and the 2010s. For the talented, cosmopolitan Fonseca—he was born in Costa Rica, spent much of his youth in Puerto Rico, and now lives in London—these far-flung locales and varied timelines serve as staging grounds for an inspired narrative about family, creativity, and self-destruction. Deftly translated by Megan McDowell, this is an intellectually fertile book, one that features an engrossing plot and several perceptive character studies.

The story starts in the suburban New Jersey home of our narrator, a natural-history museum curator. One night, as he’s preparing for bed, he sees that a package has been dropped on his doorstep. Someone close to Giovanna Luxembourg, a renowned and secretive fashion designer whose recent death is shrouded in mystery, has sent the curator a bundle of manila envelopes. You might suppose that these two ran in very different circles. But you’d be wrong.

Years ago, the curator explains, Giovanna got in touch and asked that he visit her Manhattan studio. She was working on a new clothing line inspired by animals that camouflage themselves, and she wanted to tap into his rarified knowledge. Over the course of two years, they met regularly, discussing sphinx moths, arctic hares, and wily mammals found in temperate climes. And then, without warning, “the project dissolved as spontaneously as it was conceived,” he explains. As far as the curator knows, his expertise didn’t inform any of her work, and he’s always wondered why he was summoned in the first place.

The intriguing package delivered to the curator promises to retroactively clarify the nature of their collaboration. This, though, is only the beginning. As he digs into the envelopes, he realizes that he’s looking at nothing less than Giovanna’s life story. She never told him about her youth or her family, but now, in death, she’s decided to share it all. Thus begins a set of intertwined stories that form the novel’s heart.

In one of these tales, we watch as Giovanna’s parents—American-born Virginia and Yoav Toledano, an Israeli photographer—cut a glamorous, reckless swath through boozy midcentury New York. A decade or so later, we’re in Central America, where Virginia and Yoav, with preteen Giovanna in tow, trek through a rain forest in search of a child prophet who foresees the world’s end. Decades hence, Fonseca takes us to a financially depressed town in the American heartland and a busy Puerto Rican metropolis. In the former, Yoav adopts a hermetic existence, willfully estranged from the people and work he once loved. The latter is where Virginia reinvents herself as a mischief-making conceptual artist. Living in an “immense, half-finished” apartment building abandoned by an unscrupulous developer, she attacks capitalism by placing phony financial news items in newspapers around the world. When the authorities finally realize what she’s up to, the ex-actress gets one last starring role, that of a purported criminal in a sensational trial.

Braided together, these storylines are rich and thought-provoking; in each, Fonseca’s characters are at war with conformity, engaged in a kind of self-abnegation that looks alluring from afar but, when considered up close, is messy and heartbreaking. Given her tumultuous youth, perhaps it’s no surprise that Giovanna might have hatched her own dramatic coda.

Though every so often Fonseca’s prose turns bombastic, this is a well-written, intelligent, and frequently gripping novel, an insightful group portrait of a family that finds fascinating yet tragic ways to test the limits of creativity, faith, and the law. Fonseca’s iconoclastic characters believe that if we look hard enough, we’ll see that there’s “a world beneath the world.” That may be true, but as this book reminds us, it can get awfully scary down there.

Kevin Canfield

New York